Amid Mounting Threats to Indoor Air Quality, Policies to Expand Access to Modified Box Fans Can Help

January 9, 2025

Overview

With mounting threats to indoor air quality, many public health practitioners and community leaders are looking for practical and legal strategies to improve indoor ventilation and filtration. In addition to the Model Clean Indoor Air Act, one practical strategy to make a quick and cost-effective improvement in indoor air quality – modifying box fans by adding air filters lowers the barrier to access posed by the high cost of HEPA filters and commercial air purifiers.

With mounting threats to indoor air quality (from infectious disease, wildfire smoke, home appliances and HVAC systems, industrial air pollution, and traffic-related air pollution, among others), many public health practitioners and community leaders are looking for practical and legal strategies to improve indoor air filtration. One effort toward legal reform, the Model Clean Indoor Air Act, has been written about on this page previously. This post is focused on a practical strategy to make a quick and cost-effective improvement in indoor air quality – modifying box fans by adding air filters. This is one way to overcome the barrier to access posed by the high cost of HEPA filters and commercial air purifiers.

Effectiveness of DIY Air Filtration Units

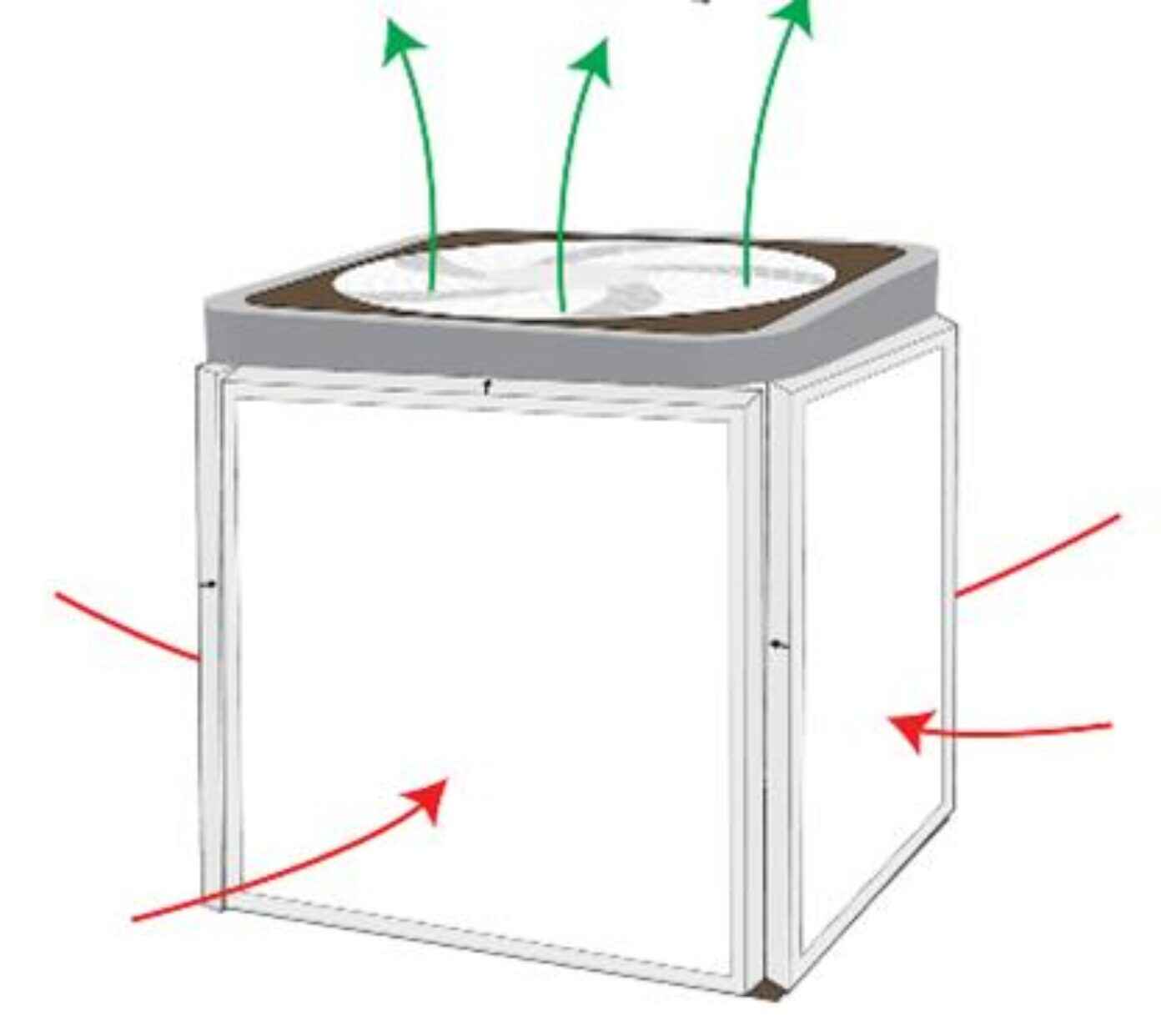

DIY air filtration units created from basic box fans were among the innovations spurred by the COVID-19 pandemic and increased wildfire smoke throughout large swaths of the country in recent years. These DIY air filtration units generally consisted of a box fan and anywhere from one to five minimum efficiency reporting value (MERV) 13 filters. A unit with five filters joined together in the shape of a cube, with a box fan attached to the top, has come to be known as a Corsi-Rosenthal box.

We now have evidence that DIY air filters contribute to cleaner indoor air by reducing the concentrations of airborne viruses, fine particulate matter, and PFAS and pthalates. Early evaluation efforts revealed a number of variables upon which the effectiveness of the units in reducing exposure to airborne viruses turned. These included the number, thickness, and configuration of MERV 13 filters, as well as the fan airflow rate. While a DIY unit with one filter reduced aerosols, the Corsi-Rosenthal box with 5 filters reduced exposure to airborne viruses even more, though at a somewhat higher cost. Implementation showed that considerations of fan speeds needed to be balanced by consideration of noise. In addition to early evidence that DIY air filters can effectively filter fine particulate matter in a lab setting, DIY air filtration units were associated with reduced concentrations of some semi-volatile organic compounds, including PFAS and phthalates.

The EPA is engaged in ongoing testing of DIY air filters outside the lab through the ASPIRE Study (Wildfire Study to Advance Science Partnerships for Indoor Reductions of Smoke Exposures). Partners in the ASPIRE Study include the Missoula City-County Health Department in Montana, the University of Montana, the Hoopa Valley Tribe in California, and other partners.

DIY air filtration units are less expensive than commercial HEPA filters but that does not mean they are the second-best option. The Clean Indoor Air Project at Arizona State University and the University of Connecticut recently published a longitudinal study of the effectiveness of Corsi-Rosenthal boxes in school settings in Arizona and Connecticut, concluding that, “the DIY filters, known as Corsi-Rosenthal, or C-R, boxes, work better than commercial HEPA air cleaners for a fraction of the cost.”

Scaling Up the Use of DIY Air Filtration Units through Programs, Policies, and Laws to Promote Health Equity

Among the strategies employed to address the potential health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and wildfires in recent years, health departments at the state and local level began providing information on how to build a DIY air filter. This strategy is included in the Health Equity in Action Playbook from NACCHO discussing best practices to address poor air quality.

Some health departments began to institutionalize this work in various ways. For example, the city of Milwaukee health department distributed DIY air filters to polling places in the spring of 2023, so that concerns about COVID would not be a barrier to civic participation. The Wyandotte County Health Equity Task Force (Kansas) identified access to clean indoor air as a priority for health equity, and included hands-on instruction in building Corsi-Rosenthal boxes as part of its outreach and STEM education offerings for youth. South Providence’s Health Equity Zone Team (Rhode Island) hosted a similar event in partnership with the local library.

Last fall, in the context of several years of legislative and gubernatorial attention to poor indoor air quality in schools, as well as the longitudinal study noted above, the state of Connecticut announced a commitment to install Corsi-Rosenthal boxes in every public school classroom in the state. The state has made a grant of $ 11.5 million, funded through the sale of bonds. to the University of Connecticut to carry out this charge. Leaders of the project explicitly note that it is a meaningful interim solution until a comprehensive overhaul of school HVAC systems can be completed.

When it comes to improving indoor air quality, there may not be a one-size-fits-all solution, at either the practical or legal level. DIY air filtration units are a low-cost, highly effective way to increase access to clean indoor air, providing protection from both communicable and chronic disease. It seems clear that the research and implementation efforts will continue, and that they will seek to address challenges identified to date, including concerns about noise and the need for replacement filters. In collaboration with community partners, public health departments (including their policy, legal, and health equity teams) can be part of the creative process that crafts strategies to scale this practical individual intervention up to a more systemic intervention.

This post was written by Jill Krueger, Director, Climate and Health, Network for Public Health Law. The Network promotes public health and health equity through non-partisan educational resources and technical assistance. These materials provided are provided solely for educational purposes and do not constitute legal advice. The Network’s provision of these materials does not create an attorney-client relationship with you or any other person and is subject to the Network’s Disclaimer.

Support for the Network is provided by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF). The views expressed in this post do not represent the views of (and should not be attributed to) RWJF.