From 0 to 50: The Rapid Adoption of Naloxone Access Laws in the U.S.

July 26, 2017

Overview

The opioid overdose epidemic is a continuing public health crisis. When we began tracking laws aimed to increase access to naloxone in late 2012, they existed in only eight states. As of July 1, 2017, every state and Washington D.C. has passed at least one law increasing access to naloxone—a remarkably rapid progression for public health legislation.

Six states and localities have recently declared public health emergencies related to opioid overdose. Over 33,000 Americans died of opioid-related overdose in 2015, an increase of nearly 16 percent from 2014. Numerous legal, policy and clinical changes have been made to attempt to stem this tide of overdose death and disability, including prescribing guidelines for chronic pain patients and the passage of two federal laws intended to improve quality of care and increase access to opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment.

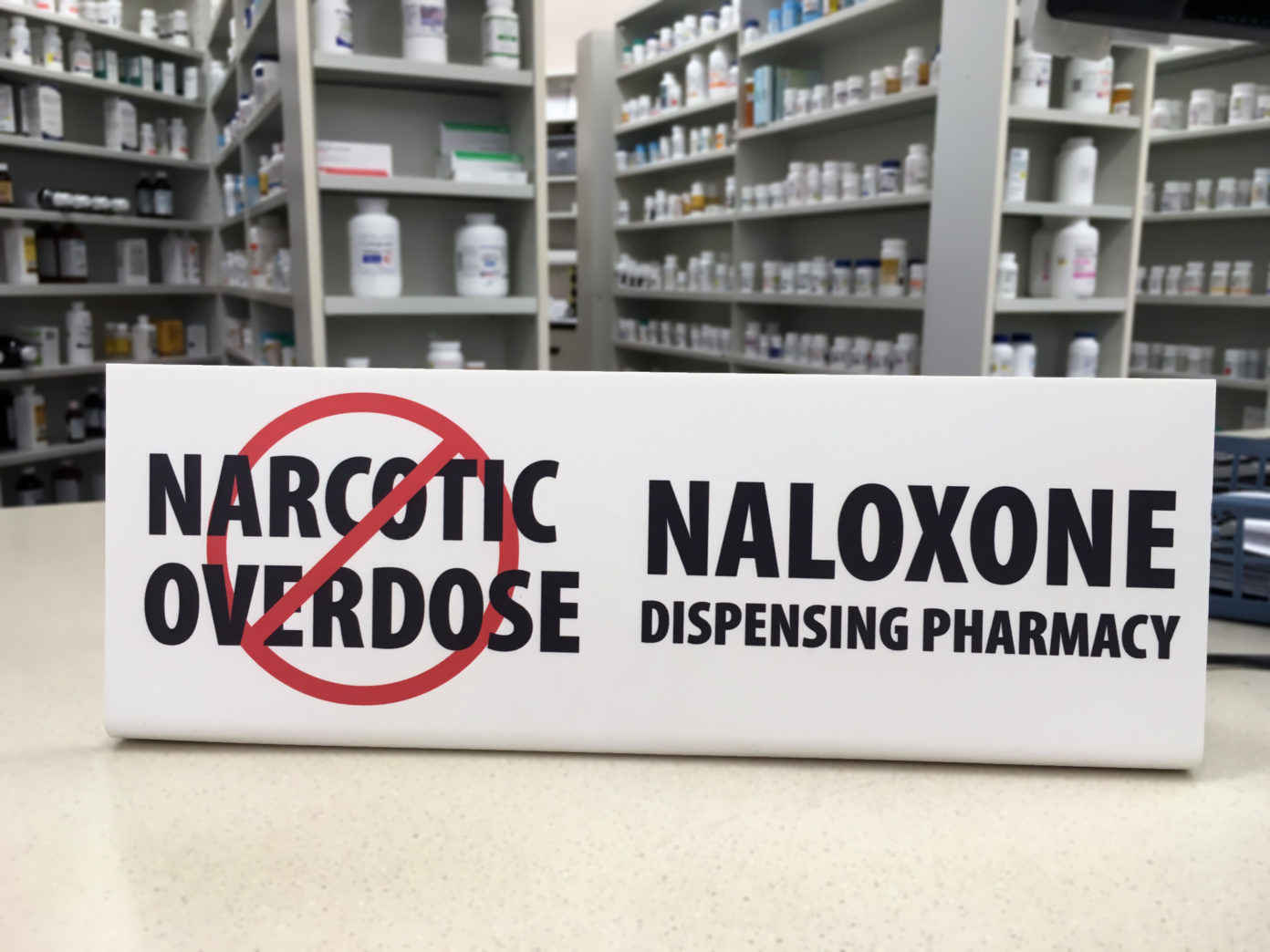

The low-hanging fruit of fatal overdose prevention, however, continues to be increased access to naloxone, the medication that quickly and effectively reverses opioid overdose if given in time. To make it more likely that this life-saving drug will be available when and where it’s needed, states have passed legislation to remove many of the barriers that previously made it more difficult to access naloxone. These laws contain a number of provisions, most notably permitting naloxone to be prescribed to people who are not patients of the prescriber, permitting “standing order” prescriptions that permit it to be dispensed to the community, and providing immunity to medical professionals who prescribe and dispense the medication.

When we began tracking these laws in late 2012, they existed in only eight states. As of July 1, 2017, every state and Washington D.C. has passed at least one law increasing access to naloxone—a remarkably rapid progression for public health legislation. In addition, 41 states have passed overdose Good Samaritan laws that provide limited criminal immunity to people who report an overdose in good faith. A recent analysis found that these laws work: naloxone access legislation is associated with a 9 to 11 percent decrease in opioid-related deaths; overdose Good Samaritan laws also decreased overdose deaths by a similar amount, although that result was not statistically significant.

In addition to passing naloxone access laws, states have taken additional steps to make the medication more available. Nearly all states permit standing orders for naloxone, and many pharmacy chains, nonprofit organizations, and government entities now dispense naloxone under such orders. Additionally, some states have also taken the step of issuing a statewide standing order that allows nearly everyone to obtain naloxone at a pharmacy without first getting a prescription from a medical provider. At least 16 states (Alabama, Arizona, Georgia, Indiana, Iowa, Louisiana, Maryland, Michigan, New Mexico, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Texas, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, Wisconsin) now have such orders, which are typically issued by the state health officer or similar official,, as do Baltimore City and New York City, among others.

Additionally, Tennessee has created a statewide Collaborative Practice Agreement for naloxone dispensing that is the functional equivalent of a standing order, and legislation in New Jersey requires the Commissioner of Health to issue a standing order on request to any qualified pharmacist who requests one. Similarly, the chief medical officer of the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment will issue standing orders on request for naloxone to be dispensed by pharmacies and harm reduction organization employees and volunteers in the state.

Naloxone alone will not stop the overdose epidemic. But making sure it’s immediately available at the scene of an overdose is a good place to start, and states have made great strides in that direction.

This post was developed by Corey Davis, Deputy Director and Senior Attorney, at the Network for Public Health Law – Southeastern Region Office. The Network for Public Health Law provides information and technical assistance on issues related to public health. The legal information and assistance provided in this post does not constitute legal advice or legal representation. For legal advice, readers should consult a lawyer in their state.

Support for the Network is provided by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF). The views expressed in this post do not necessarily represent the views of, and should not be attributed to, RWJF.